Welcome to In Conversation, a special interview column on the site where we sit down with artists and dive deep into everything music. Dobbin chatted to ameokama about their most recent record, a track-by-track analysis and themes across her record i will be the clouds in the morning and the rain in the evening.

Powered by RedCircle

Dobbin: You’re someone who has a lot of credits on different releases—you’ve recorded with all sorts of bands over the years, and you’re also a producer for Newhouse Studios. How does it feel to finally have a record coming out that is 100% you?

Aki: It’s really exciting but also nerve-wracking and vulnerable for that exact reason—because it’s 100% me. It’s the most honest and candid image of myself that I’m putting out there. Pretty much everything else I’ve worked on has been collaborative to some degree. This album does have collaborations, but most of my previous releases have been as part of a band. With this record, there’s a lot of pressure because, however people perceive it, they’re perceiving me.

Dobbin: I completely get what you mean. I really love this record. It’s sonically broad, and you used the term “vulnerable”, which I think applies not just in terms of the personal, open nature of the lyrics but also in how it defies genre expectations. The record covers so much ground stylistically. Some listeners might connect with certain tracks more than others, but for me, I’m here for the journey. What drove you to make something so sonically diverse?

Aki: Having been in so many bands, there was always some amount of pressure to have a clearly defined sound. I was never the sole person in charge of the band’s musical direction, and other members might say, “I’m not really into that”. Over the years, whenever I heard something I loved, I’d think, “I need to make a band like that! I need to try that!”. I never had the space to fully explore all those styles in any other band. Part of making this album was about letting myself explore those sounds—creating something that didn’t feel like it could belong to any of my past bands.

Dobbin: Even though it’s sonically broad, I can think of other records within this sphere of experimental or “weird” metal that do similar things—where the music shifts dramatically between tracks. But I think we don’t see that approach often enough. There are plenty of albums that sound like a band playing together in a room, but not enough where it feels like the band is shifting between different worlds—one moment they’re in a room, then in space, then underwater. This record takes the listener through those kinds of places. In terms of your past work, what’s the closest you’ve come to a 100% “you” record before this?

Aki: I’d say my past records were snapshots of who I was at the time. This one is a snapshot of who I am now—hopefully a more fully realized version of myself. There were two albums where I had the most control: the first Vivid Illusion album, Cyclical Nature, which I had been writing for five or six years before finally bringing it to life, and Volume 3 from A Constant Knowledge of Death.

Cyclical Nature represented one side of my musical taste—the ambient, post-rock, post-metal, and doom influences. That album was pretty much entirely written, recorded, and mixed by me. Volume 3, on the other hand, was part of a project where each band member wrote their own mini-album. Mine blended my love of technical, riff-heavy music with atmospheric and doomy elements. That record was probably the bleakest and angriest thing I’ve ever written. It came out a year before I started transitioning, and at the time, I felt like I had no future. Writing it was a way to lash out at the world. Now, I still write songs about fighting oppression, but from a place of knowing there’s so much to live for.

Dobbin: Diving into this new record, I thought we could go track by track since it really feels like a journey. The first two songs in particular feel very cohesive in both sound and theme. You did not hold back! These are intense, deeply personal, and also explicitly sexual tracks. They’re wild. I think people are going to immediately recognize that this album has a strong and conscious perspective. I love how you embrace electronic elements alongside the gritty textures. What were your motivations for these first two tracks?

Aki: I really wanted to overwhelm people. Interestingly, I wrote most of this album backward—”my fears have become fetishes” was actually the last song I wrote, and I struggled with it the most. I had a couple of drafts, but every time I tried to write it as a metalcore song, it felt uninspired—just riff soup with vocals on top. I wasn’t motivated by that. The turning point came on the day my first single was released. I was out with my roommates, and they showed me a Nightcore/Alvin and the Chipmunks version of “Call Me” by Blondie. It was so moody and dark in a bizarre way. Something about it clicked. I got home and wrote the entire song—lyrics and all—in about 10 or 12 hours. That was the moment I knew it was right.

Dobbin: I love lyrics that challenge God—or, in your case, invite God to perform sexual acts.

Aki: That line references multiple things—the writing process, transitioning, and rejecting the idea that I have to conform to what’s “natural.” Some people say transitioning is unnatural, but I don’t care. I’m choosing to shape myself into the fullest realization of who I want to be, even if it involves artificial means. And I’m doing it both for self-actualization and out of spite. Another big part of this song was capturing that flow state—the feeling of being so immersed in creation that you’re almost feral. I wanted to depict that as both sexual and violent.

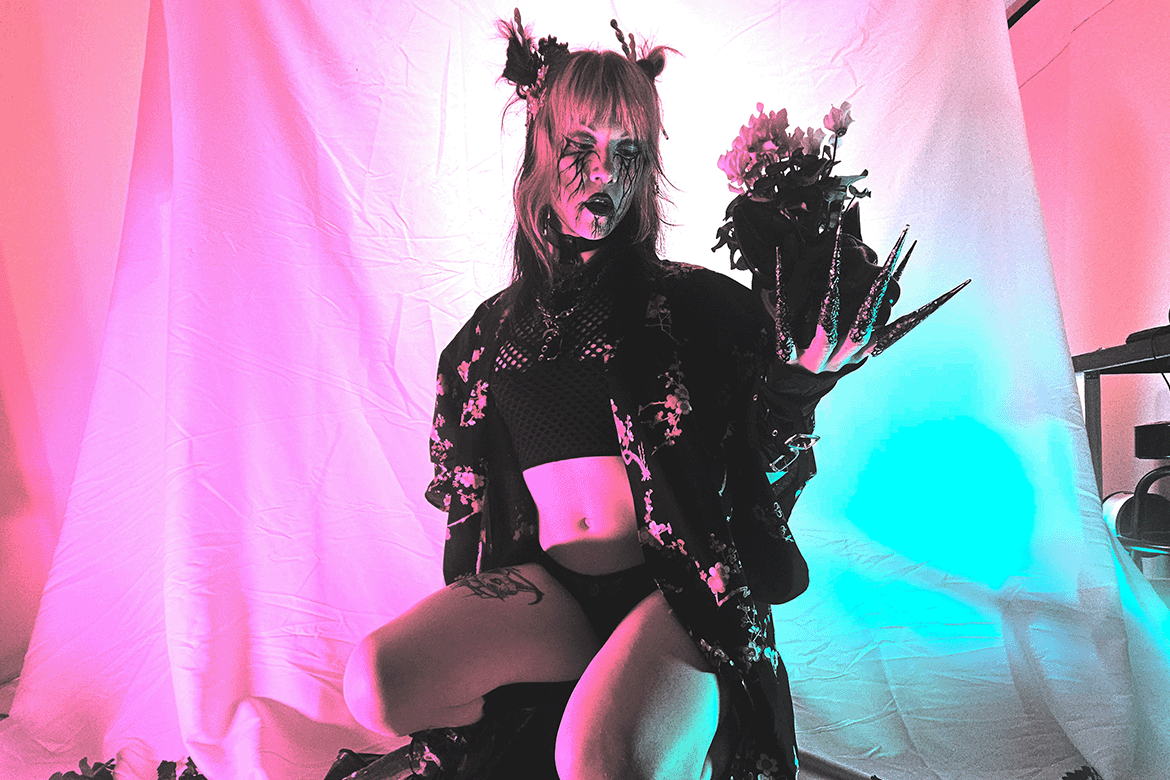

Dobbin: Moving onto “phantom cock”, the video looks fantastic, especially the glow-in-the-dark paint.

Aki: Oh my God, it was so sticky! We used a fake blood recipe but swapped the red dye for green and added glow-in-the-dark powder. Cornstarch was everywhere. I had to shower between scenes just to get through it.

Dobbin: Visually, it really enhances the surreal, nightmarish vibe of the song. “phantom cock” takes the themes of the first track and pushes them further into the grotesque and theatrical. Lyrically, it’s intense—there’s this push-and-pull between confidence and anxiety, power and vulnerability. What was the inspiration behind it?

Aki: This one came from a really visceral place. A lot of my music explores identity and dysphoria, but “phantom cock” specifically plays with the idea of embodiment—what it means to claim a body that doesn’t always feel like yours. There’s something both empowering and absurd about that. I wanted to capture the sensation of fully stepping into yourself but also the lingering ghost of past selves that don’t quite disappear. That’s why the imagery is so exaggerated—decay, mutation, artificiality. It’s grotesque, but it’s also affirming.

Dobbin: That makes so much sense. The way the music shifts, too—it’s like the song is morphing in real time, which really drives that idea home.

Aki: Exactly! I wanted it to feel unsteady, like it’s constantly shifting between states. That’s a big part of why the electronic elements are so pronounced—they give this sense of something unnatural yet inevitable, like a machine reprogramming itself.

Dobbin: The way it feeds into the next track feels like a hard reset, almost like coming up for air after being completely submerged. I want to get into that next, but before we do, was there anything else about the video or recording process that really stood out to you?

Aki: Honestly, just how freeing it was. Making this record, I gave myself permission to be indulgent, and that extended to the visuals. The shoot was chaotic, but it felt so cathartic. I think that energy really comes through in the final result.

Dobbin: It absolutely does. Okay, let’s talk about Track 3, “i am driving a car with a cute girl pretending that the world isn’t ending”.

Aki: That was another one where I wanted the surface energy and the emotion, but not very deep under it, to contrast a lot. And yeah, that’s pretty much spot on—on the surface, it’s a fun song about driving around with a cute person, but there’s a lot of melancholy underneath. That was another one where I came up with the title first, when I had that initial vision. A big part of making this album and going through my own self-discovery was about bringing those visions to life—figuring out what they truly meant.

A lot of the time, I’d think a song was going to be about one thing, and then it would evolve into something entirely different. With this one, I really wanted a muse. I wanted to write a cute love song about meeting the love of my life and driving around with her. And for a while, I kept having these moments where I’d think, “Oh, she’s the one, This is the person this song is about”. But that feeling never lasted.

That’s where the line in the chorus—“Your face shifts shapes as you ride next to me”—comes from. The song isn’t really about any one person; it’s about the idea of a person. And the reason for that is embedded in the title itself—it’s about having this dread about the future and trying to ignore it through intimacy. It’s the feeling of wanting to find someone to ride off into the sunset with, to make everything feel okay, but realizing that no one person can actually fill that void for you. It’s about moving from person to person, looking for that fix, that distraction, and having to confront the fact that sometimes, in that process, you’re not being your best self.

Dobbin: I do hope you find your cute girl to drive around with—you deserve it.

Aki: [Laughs] Part of it, too, is realizing that throughout the process of making this album, I was searching for something external when, in reality, it’s me. It’s cliché, but I’m the cute girl. The girl reading this—it’s me. It was about learning to sit with myself, to confront my feelings alone before I could fully share my life with someone else.

Dobbin: And that’s why the single cover is you twice, right? Like, me and the girl reading this.

Aki: Exactly.

Dobbin: Let’s step into the next tracks. “ravensong” sort of works as a really short interlude into “izanami”. What’s the meaning behind it?

Aki: That one is actually about something very specific—and probably heartbreaking for people to hear. It’s about my cat, Raven, who passed away in 2022. She was a Sphynx cat, and I got her in 2019. She was incredibly important to me, especially during the early stages of my transition. That period coincided with COVID, when I felt especially vulnerable. It seems obvious in hindsight—of course, a cat doesn’t care about you wearing makeup or different clothes—but for some reason, that was really reassuring to me.

The song is about having that kind of guardian angel during a very specific moment in time and the longing for more time with her. But ultimately, it felt like she somehow knew I’d be okay on my own. As the noise feedback starts coming in at the end of the song, that feeling of uncertainty intensifies—leading directly into “izanami“.

Dobbin: Onto “Izanami”, which reminded me of the Victory Over the Sun record you recorded and contributed to, but I find it really interesting that you actually wrote this song way back in 2015—before this project even existed.

Aki: Iit took a while to find the right place for it. I actually released an earlier version on the compilation Trans Rights or Else, but I completely remixed it for this album. One of the reasons it might sound somewhat similar to Victory Over the Sun is because both were inspired by similar influences—especially Liturgy, with those relentless tremolo guitar lines. The chord progressions feel very much in the tradition of late 19th- and early 20th-century classical music—romantic and modern era compositions that just keep expanding instead of repeating. Another big reference point for me was the black metal band Nánafaxa.

Lyrically, the title “izanami” comes from Japanese mythology. She’s the Goddess of Death and was originally part of a creation duo with her husband, Izanagi. When she died in childbirth, she was trapped in the underworld, similar to the Orpheus myth in Greek mythology. Izanagi tries to save her, but by then, she’s eaten the food of the underworld and is doomed to remain there forever. Her body rots—her eyes fall out, maggots consume her—and when Izanagi sees her, he’s horrified and abandons her. In response to this rejection, she vows to kill 1,000 people a day, essentially creating the concept of death itself. Izanagi counters by creating 1,500 new lives a day, establishing the cycle of life and death. To me, the idea that someone handled rejection so badly that they invented death itself is just… profoundly metal.

On a personal level, the song interprets this myth through my own experiences with suicidal ideation. The lyrics depict a relationship between me and Izanami—she appears in my teenage years as a shadowy presence in the corner of my room, and over time, we develop an intimate, almost addictive relationship. She tries to lure me with her, and I tell myself I only need a “fix” of her presence to keep going. But eventually, she knows I will be with her forever. The final line, “She is patient, for I have eaten at her hearth“, signifies that I’ve already sealed my fate—I’ve consumed the underworld’s fruit, meaning I can’t be saved.

Dobbin: I find it fascinating how this song, which has existed in different forms for so long, carries that weight through the years. On a different note, I was surprised to see “Copernicus” in the track listing. When I first listened, I had this slow realization—”Wait, I know this song!“—and then when the chorus hit, it all clicked. It’s such a deep cut from The Mars Volta. You must be a serious fan to choose this one.

Aki: Yeah, I’ve always loved this song. I connect a lot with the more ballad-like moments in The Mars Volta’s catalog, and Cedric’s lyricism has been a big influence on me. He has this unfiltered way of writing about wild, surreal concepts, and I admire that.

The reason I included this cover on the album is personal—I had planned to record it with someone I was dating at the time. When that relationship fell apart, I still wanted to include the song because it resonated with what I was going through. It feels like a convoluted breakup song, and that fit perfectly within the album’s themes.

Musically, I reinterpreted it in a more slowcore style, influenced by Low and Midwife. I also lowered the key slightly—it’s already a moody song, but bringing it down just a half-step made it even more melancholic. The electronic sections were fun to experiment with, too—I love distortion, so I leaned into that to make the production feel more industrial.

Dobbin: Speaking of distortion, let’s talk about “cluster B”. This track stands out as one of the noisiest on the record. It’s not complete wall-noise, but there’s definitely some intense, harsh elements. What I appreciate is how you blend different textures—there’s this underlying drone or pad, and then the sharp, frontal noise layers. It works really well. And then, at the end, if any Skrillex fans are wodering “where’s the drop?”, we get this brief doom-like section. It feels like it’s always building up to something—almost like it’s threatening to explode into noise.

Aki: This was one of the earlier tracks I worked on for the album. It started on a day when I was having a mental breakdown, unable to focus on anything else, but I needed to create something. I made the bass synth, and then layered all the other sounds on top. There wasn’t really a clear vision or words for it at first, just that feeling of mental chaos. That’s why the ending is mostly just screaming into the mic, with a wall of distortion and feedback. I think I have a video of it on my Instagram somewhere, where I’m just in a dress and makeup, screaming like a demon. A lot of that track was improvised on the first take, and then I revisited it later, not quite satisfied. Sylvia Haynes ended up adding some amazing bass drones and saxophone layers that really brought it to life. I’ve worked with Sylvia on mixing and mastering before; she’s a brilliant composer. She sent me tracks with about a hundred string layers that sounded like a huge orchestra, even though they were recorded in her room. It’s been a huge inspiration for me, and I owe a lot to her. She really helped add atmosphere to this track. I also layered live drums, bass, and guitars at the end to give it some fresh textures—very much inspired by bands like The Body, who mix electronic and doom metal in such an interesting way.

Dobbin: The Body is a fantastic reference. I had the chance to see them live with This Will Destroy You on a UK tour, and their collaboration was incredible. I love how they merge drone with other genres, especially metal.

Aki: Oh, that would be a dream collaboration for me. They’ve worked with so many amazing artists. While their albums on their own are fantastic, it’s their collaborations that really highlight their versatility.

Dobbin: Let’s move on to a very different track, ”i will be the clouds in the morning and the rain in the evening”.After the intensity of “cluster B” and wierdness of “copernicus”, this track offers a moment of harmonic relief. It’s the most harmonious track on the record, and it introduces the piano, which becomes a key element in the next song. It’s also a bit of a doomgaze track—heavy yet beautiful. And it’s our last track with significant lyrics. Would you say it’s the closing chapter of the album? What’s the song about, and what does its position in the tracklist mean?

Aki: That’s a great way to sum it up. It’s almost like a title track, not just for the album, but for the project itself. The title ameokama from a Japanese yokai named Ameonna, a spirit of rain. She’s often seen as an evil entity because wherever she goes, she brings rain, turning mourning souls into rain demons. But at the same time, she’s necessary—rain is vital for life and the ecosystem. So, the track mirrors that duality. It’s about someone who feels like they’re spreading negativity, but also acknowledging the necessity of that darkness. The song itself tells the story of an encounter between two characters: one knows they’re going to be harmed by Ameonna, but they don’t care because they’re lost in the moment. The second part is from Ameonna’s perspective, feeling the weight of spreading suffering.

Dobbin: There’s a personal element to this too, right? It feels like it mirrors your own experiences with the idea of a dark force, which you start to accept. Do you feel that way in relation to the album, like it’s about coming to terms with something darker?

Aki: Exactly. The personal connection is in that second part of the lyrics. It’s about feeling like wherever you go, you bring clouds, darkness, and rain—spreading negativity and sorrow. And while others may grow and heal once you’re gone, you feel like you’re meant to be a negative force to be overcome. It’s about recognizing that cycle of self-doubt and understanding its role in your life.

Dobbin: Moving on to the final track, “gila river”. It’s a piano-driven track, almost ambient, and it’s beatless, which creates this trance-like atmosphere. It feels like the song was built around the piano, with layers gradually added on top. It’s a fantastic approach for ambient and drone music. Who played the piano on this track? Was it you?

Aki: Yeah, it was me. That’s exactly how I created it. I had a few melodic ideas and a loose structure in mind, but I recorded it in one take with no metronome. I wanted to capture that natural ebb and flow. Then I built the rest of the arrangement around that, adding noise, guitars, and layers. Sylvia also contributed here with some bass drones and textures that really gave the track depth.

Dobbin: The piano definitely adds this ethereal, almost peaceful quality. It’s a pretty sound, but it doesn’t feel like a happy ending. The track closes with a short sample—does that sample have lyrics? And what’s the significance of the title “gila river”? I had to look up where it is—it’s not near where you live.

Aki: Yes, the sample has lyrics, and it’s actually very personal. On my mom’s side, my family were detained in the U.S. during World War II, part of the internment of Japanese Americans on the West Coast. “gila river” was one of the camps where my family was held. The track reflects on that experience—the generational trauma that still affects people today—and serves as a reminder of how easy it is for fascism to rise again, with vulnerable groups being targeted.

Dobbin: I love how each song on this record feels distinct and diverse. You’ve really created a dynamic listening experience, where the listener is challenged to value each track, no matter how different they are. It’s not just about “I liked this song more” or “I liked that song less”, it’s about appreciating them in a deeper way. I know you’re interested in bringing this to the stage. Do you have any plans for live shows?

Aki: Yes, definitely! It’ll be challenging, but I’m planning to do a mix of live band performances and solo sets. The solo sets will focus more on improvisational, ambient, and noise elements—things that might not sound exactly like the album tracks, but will have the same creative spirit. For the more structured songs, I want to perform them as well.

Dobbin: I’d love to see that live. Even if it’s not near me, it would be amazing to experience it. I can imagine the technical challenges, though!

Aki: Yeah, definitely. But it’ll be fun to put it all together. It’s just a matter of figuring out how to make it all work.

Thank you to Aki for sitting down us with us, you can find i will be clouds in the morning and rain in the evening here.